They say people ask for money in Africa. In Zambia kids and grown ups looked at us with curiosity. They might have not had a clear idea what on earth we are doing by just traveling, but never asked for anything.

Arriving to the one of the least developed countries in the world, we perhaps had to expect something different to happen. But not as soon, not even before entering Malawi. The official who sorts out the documents at the border calls his boss to inquire about this or that, something he should have known himself. But for him it perhaps was the job of the year, so he started somewhat painfully mew that Easter is coming and we might want to help him with something. ‘Religion doesn’t allow us’. Well, if it doesn’t then yeah.. The last time we have been asked so openly to contribute personally to policemen coffee break, it was in Kirghistan, when they caught us after sitting on the grass in the middle of the city.

Hundred meters later the money begging marathon begins. ‘Give me my money’ the kid screams, surrounded by another six. The world famous cyclist around the world A. Humphreys while on his ride through Ethiopia after having experienced something similar made jokes that he might be old fashion, but good morning it is still the polite way to greet each other. We ask why they need that money. The answers from here on start to vary. The shepherd wants coca cola, kids desperately need biscuits, a guy needs a new roof, a school would be happy to receive some scholarships, and a happy fisherman would be so much happier somewhere in Europe. Even in cold Lithuania we guess. We are walking white ATM machines, who could deliver some cash here and there. To make Malawi happy. Or is not? We shall try to sum up our impressions rightly and peel one layer after another down till the core. Why Malawi is still sick, and does he need medicine, or would he be able to recover itself. We will share not only our observations but give some other people’s accounts too.

Griffin – we need business opportunities

After being picked up on the way towards Malawi lake from Lilongwe, Griffin has been the first one to get deep down into conversation what Malawi problem is after all.

Griffin works for Go!Malawi organisation funded by USA and offering scholarships to talented young people. He was telling us ‘when we came to the region we had a hard time working with the community. We offered them education opportunities instead of just doling out cash like previous Scottish people did. So we are the bad ones. It has been hard to bring them to understanding we have other options for them’. Malawi has been getting donations for entire of his independent existence, and the situation did not improve. So you just start wondering what is the problem. It seems that the government is happy not to have educated intelligent people. The gray population should rather be uniformed, peaceful and nice, but oblivious to the situation. People end up not working as they do not see any need for that. Why to work if the western organisation or government will come and sort all the problems. ‘We need business opportunities like they do in Mozambique or Ethiopia, but not donations. Some charity organisations get the money but spend 75% of the budget on administration, and only the rest goes to community. Like the previous administrator instead of spending Go! Malawi money for the orphanage is in the parliament now, as the money served well to make a nice political campaign and get a good car’ Griffin tells.

You would think, that if people do not want to work maybe they don’t need money. But they want to get rich, so then witchcraft comes in hand. The go to the witches and are ready to do what he or she orders them to: to sleep with their children or parents, dig out the dead ones or mutilate an albino. Instead of working hard some powers should come and help. So either western world or witchcraft. But what about their own dignity and the joy of the work, however socialist it might sound.

Džiovinamas tabakas, viena iš kelių pagrindinių pajamų šaltinių. | Drying the tobaco leaves. It is one of the few local people money incomes.

Griffin offers us to stay for a day in one of the organisations tiny houses, and we can rest our eyes down the hills and Malawi lake in the distance. A day later we decide to continue our journey by walking the unpopular no tarmac path knowing the fact that the cars will be a rare thing to witness. Walking through the villages might give us a better feeling of how really people live.

Our Malawian day to day life

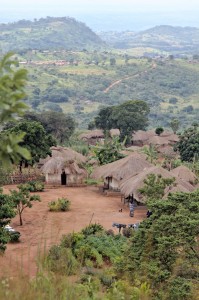

Eighty percent of Malawians live in the village, so the country being so cute in size, even the bushes were densely populated with small communities, clay houses and hay roofs. You only need to step away from tarmac road and you will find yourself fully submerged in the rural life.

Arbatos ir bulkos užkąst į kaimo arbatinę. | Tea and bread break to the small tea house by the road.

We walk in to the tea room in one of those small communities. The cement house with some shelves holding loaves of bread and plastic cups and plates. The owner soon pours us Chombe sweet tea and breaks the best part of the white bread. We are utterly relaxed and happy as if we have drank the best latte or eat the fancy cake somewhere in the big city coffee shop. The people under the shed look inside in as they curious but pretend to continue their table (or better to say bench) games. Some kids are looking at us from afar. We continue our journey buying some local bananas or tomatoes on the road and passing one of those well fenced pubs where locals go to drink some beer.

We stop at the tobacco leave dry sheds. The women sit around sorting the leaves, and the guy hangs them out in the shed. Tabacco here is the green god, the most exported good to outside world. Unfortunately, locals complain, the Europe and States do not smoke as much, so they loose the business.

If one kid spies that azungu passing the village he would run screaming on the top of his lungs and we can see now how the tribes ages ago might have been able to communicate. The echo waves through the village, so now kids coming out of bushes, houses, corners and nowhere, and then it all starts. Whats your name, can you give me money, We are not talking about couple kids, we talk about crowds and crowds. We might not sound very loving here, but couple days later we are exhausted from the attention and after hearing another azungu our mind just goes blank. In the evening they help us mount our tent, our personal house they might have never seen before. Once we even employed a local teacher and a policeman to mount it up. ‘Kids will disappear after dark’ he reassures us as they would follow every step of our unpacking and stay there as long as it gets dark. From the early morning they right here to observe our morning routine. Lets just say that community life means no privacy and space, but then there is some charm enveloped in that too.

We continue our journey. The previous days the walk down the hills got on us pretty hard. We looked rather like robots not oiled for some time, so every time we rose on our feet we looked rather old, and elderly village men were overtaking us and waving youthfully back. Ok, we have heavy loads on our back, so we don’t feel so down. Or at least that is how we try to cheer ourselves up. The midday sun is aggressive, so by the end of the refreshing sunset you feel a bit exhausted.

During one of the frequent breaks to stop under the tree and have a rest, a guy cycles by and he (as hundreds of others) wants to know who we are and all that stuff. We are walking. Oh, sorisorisori he moans. How can I help you. He ends up cycling home, bringing a bowl of peanuts and giving it us. Oh that is a surprise. After all this being a cash sack we were looked at differently. He didn’t show his teeth so we could chip in with some cash to fix them, he did not ask to put a roof, to bring to Europe or to get him a passport. In fact he was the noble one to offer what he has. ‘I’d like to stay with you longer but im off to the funeral’.

Indeed the road seemed to get packed with people. Women were carrying plates wrapped in colourful patterned scarves on their heads, and men walked separately in small packs. We soon came across a household where all the villagers gathered as one of their community members passed away. So the yard was filled with steaming pots of sima (maize porridge) and vegetables, and meat perhaps as they only eat meat during the festivity time. We sat not far from the house where men and women were singing songs. Being a silent witness of the rural life was one of the best (not the easiest) experiences. You come to a point where you actually feel you are in a different reality, and you are not going to get out of there.

Smalsios moterys nešančios skalbinius. Neįtikėtina kiek ir ko jos gali panešti ant savo galvų - nuo maišo apelsinų iki ilgų ilgų lentų namui. | Women carying the washed clothes. It is increadible how much they can carry on their heads.

Those days of walk made us into soft cripples, and when we heard the car sound from afar, we decided it is the time to hitch. Father Fernando, Spanish missionary who stayed in Africa longer part of his life than back in Europe, not only gave us a lift. We also stayed in his place, had meals together and had a chat what is the situation in Kenya, as he has been living there for those twenty years, hence being fresh in Malawi. ‘What are the issues out there’ we inquire. ‘AIDS is huge as everywhere else, and thanks to myths the situation is not improving as rapidly as one might wish. But sexual and moral education seem to help people understand more about themselves’. Father gives us the contacts of where he used to live in Kenya, sister Grace gives us a huge hug, and the next day we set off to the road. North alongside the lake of Malawi. We keep on walking when the road is empty, and jump on the back of the truck to move those couple or twenty kilometres. But we feel moving.

Clarissa – Peace Corp volunteer: ‘There are two solutions to save Malawi’

‘Are you walking to fund raise money?’ asks Bob Marley’s copy all smiling and happy. ‘Ah, nah, we are traveling on our own, just to travel. We are a bit of egoists we guess’. ‘Oh no, those who do the walking do little good for the country’ made a comment Klarissa, a Peace Corps volunteer living here in this country for nearly two years. She has been finding it hard to start with as the male health specialist at first would not even thought to take her as some sort of good asset to a team. Women here are of lower species. After all this time she has spent here, she feels she could helped like fifty people only. Living as a part of community helped her to be supported psychologically, as the others working purely with projects were often down to achieve fast results.

‘We have heard and read that some authors and journalists are against the all sorts of organisations who only can do more harm than good. Is that the case, according to your observation and experience?’ She could see many of those organisations building all sort of houses and leaving them empty, and so the meant-to-be school going

So what would the solution for Africa be then? Clarissa has two options in mind. Either stop donations entirely, and surely it will lead into quite a big disaster for a while. But then people would wake up and start doing things on their own. Or change the education system. For the government is so useful now to have a society which is calm and peaceful, but not understanding where the problem lies. Also, to show it’s handy to show the donor countries, how poor people are and how needy is the country in money. So the vicious circle never ends. And like fifty years ago people keep on saying how poor is the Africa. But the land is fertile, and things are possible to grow and do.

Crock from Zimbabwe: ‘If you lived there you would think like I do’

Mus kelyje pavežėjęs Zimbabvės baltasis rodo savo vaikams kaip gimsta guma. | A man from Zimbabwe that gave us a lift showing his two kids how the rubber is born.

‘Jump in, Ill give you a ride to Nkhata bay’. Further than that. That day we made it even more North, to Nyika plateau with Crock and his two boys. We managed to visit rubber factory on the way, see the hot springs (locals have not had made it into business yet), and splendid views of Northern Malawi – mountains and valleys.

Crock has come from Zimbabwe, where he was born and raised. Now he has come with his kids to visit Malawi, as the situation in Zimbabwe is getting rough. Just some years ago his family was thrown out of their land. ‘We bought the land, we didn’t steal or anything, we took mortgages to build things and gain profit. But Mugabe let the people simply come and destroy all we had. So one day they just had to leave, and everything that has been left behind, was destroyed – houses, machinery’. They had 1000 cows and 3000 ostriches. Then they had to start from the scratch, but it seems the new business seems to be threaten once again. Mugabe totally wants to get rid of whites. ‘I guess every white would start feeling something similar if they arrived there and went through the same thing’.

Talking about these painful issues Crock came up with the idea to visit rubber factory somewhere away from the road. Amazing, we have just seen how the rubber trees been cut and white liquid accumulates in cups, and now we see the entire process of the rubber been in the acid water looking like fetta cheese, then going through the drying time in some smoky rooms.

One really good thing what Crock us taught about was the Bilharzia, some bacteria can be found in Malawi lake. We swam in the lake twice so we better take the pills against it. According to him, there are sort of worms that can get into the organism through your under nails, and can make lot s of harm. He had the problem himself. So we quickly dropped in to the local pharmacy to get the number of pills (according to your weight) and do it all in once in few week time to avoid the danger. Apparently the bacteria is caused by locals pissing in the water. Nice one.

We said goodbye to Crock just at the turn to Livingstonia. Nyika plateau has its splendour, but that means that the banks of lake will be touristy. We find a school nearby, and so the usual business asking whether we can stay in the yard. The headmaster seems a very intelligent person, even knowing that Lithuania used to be a part of USSR as he learned that in the primary school. The deputy was a nice guy too, but we guess we fall into the same trap. We are white so eventually we will be asked for contacts in Europe or dollars for kids scholarships. Whether we are interesting? Not really, as we are not carrying cash with us. We are invited for a dinner, and thats a lovely thing. But knowing that this is made with a special intention just brings us back a nostalgia for Asian times, where people used to host us with no intention of getting something back from it.

Fredd and Happy: don’t give us money

‘This is the first time I’m taking a white person for free. I can allow myself to do it’ says a driver Fred. After having asked a usual question of how is Malawi, they start a discussion about how a kwacha (Malawian money) is getting more and more devalued, and so economy goes down. So whats the solution, we ask for Malawi to get up from the ditch and finally be independent in their process of development. ‘Don’t give us money’ we just looked between ourselves and nodded the heads. It seems more intelligent people realize what is the problem. ‘It’s in our heads now, that we don’t need work because why would you need work if a white person will come and give us something’. The education would help. The final stroke of conclusion stuck in our minds.

Malawi involved heavily in all possible ways. We walked the roads less travelled and saw people’s lives from very close. Sometimes we got into sincere and honest discussions about how Malawi could go beyond the donations, and often we were seen as a way to get more prospered. We started with an official and kids asking for money, and finished the part with some local people saying that whites should not give the money. Despite all facts discussed above we have noticed that Malawians are happy people… Will they get happier by having more things in the form of prosperity, we don’t know. I guess we will fall back into the same old discussion what is happiness after all.